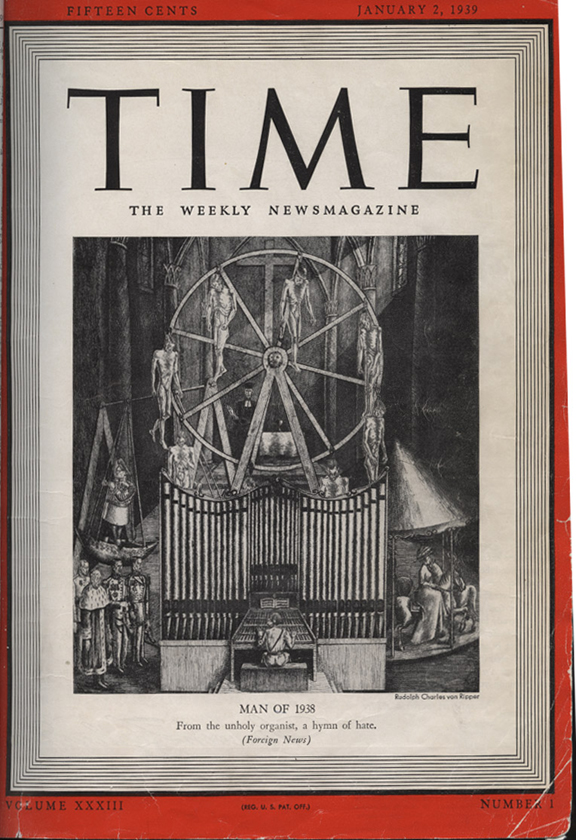

Here he is on the cover of the New Year's issue of Time Magazine on January 2, 1939: Yes, the Man of the Year just passed was Adolph Hitler, shown here from behind at bottom center. Drawn by an Austrian artist who had himself endured three and half months in a Nazi concentration camp, Hitler is here portrayed as an "unholy organist" playing a "Hymn of Hate" in a desecrated cathedral. Unlike every other New Year's cover in the history of Time, this one does not show the face of its subject. Viewed from behind at the base of the picture and dressed in his Nazi uniform, he sits beneath the pipes of a gigantic organ supporting a medieval instrument of torture known as a St. Catherine wheel. Though this method of execution ended in Germany about a hundred years before Hitler's time, the fate of the emaciated figures shown hanging from the wheel in this picture fittingly represents what Nazism had already done to thousands of its victims by the end of 1938.

In this picture, the pipes of the organ played by Hitler fittingly support a wheel of torture. More than any other dictator who came before or after him, Hitler gained and kept his power by means of his own vocal pipes: by a torrent of speeches whose manic stridency mesmerized his hearers and made them almost worship him as a god. No wonder von Ripper placed him in a desecrated cathedral rededicated to the religion of fascism, whose very name derives from the bundle of rods (fasces) so vividly evoked by the close-bound vertical pipes of the organ.

Looking back now at Adolph Hitler and his utterly ruthless lust for powerand territory, Lebensraum, what is truly uncanny is to see how much of what he did in "the long 1939" has been re-enacted in our own time by Vladimir Putin. In the 1930s, Hitler gained power by exploiting German resentment at the terms of the Versailles Treaty, which severely restricted what Germany could do. But in March of 1936 Hitler defied the treaty by re-militarizing the Rhineland--and guess what? nobody stopped him. In our own time, Putin has done everything possible to restore the Soviet empire that was humiliatingly dissolved by the breakup of the Soviet Union. In 2014 he simply decided to sieze the Crimean peninsula, and guess what? Nobody stopped him, which is a big reason why he set out last February to conquer Ukraine--or reclaim it, as he would say. Just before Russian troops invaded that country on February 24, he declared that he aimed to "liberate" ethnic Russians from the neo-Nazi tyrants who were running Ukraine. In saying this, he used almost exactly the same words that Hitler used to justify his seizure of Czechoslovakia in October of 1938. Just before invading the northwest frontier of that country, heavily occupied by ethnic Germans, he charged that these three million Germans were being "tortured" by the Czechs and that he was going to rescue them. That was a big lie--precisely the lie echoed by Putin. But Putin's attempt to sieze Ukraine has run into major resistance. Unlike the Czechs, who simply gave up their country under pressure from Britain and France, and unlike the Poles, who surrendered to Germany after just a few weeks of bravely resisting in September 1939, Ukraine has been fighting back against the Russians for nine months. It has suffered great losses of life and property from Russian bombs, but with the aid of weapons furnished by its western allies and under the truly heroic leadership of Volodimir Zalensky, Ukraine gives us every reason to hope that it will survive and preserve its independence.

But I'm not here to foretell the future. Instead I want to re-examine the past--and specifically what I call three variations on the fateful date of September 1, 1939--the day on which Hitler launched World War II by invading Poland.

The first of my three variations is not a work of literature but is nonetheless a riveting eyewitness account by a Polish officer named Jan Karski. On the day Hitler launched his invasion of Poland, Karski was just 25 years old and serving as a Lieutenant in the Polish Cavalry. At 5:00 AM on September 1, just before German bombs would cleave the clear and balmy skies over a Polish army camp near the factory town of Oświȩcim, about 40 miles west of Krakow, Jan rose from his cot.

Expecting yet another uneventful day, he stooped over to peer into the bathroom mirror and carefully shaved a face still carbuncled by some adolescent acne. At 5:05, almost before he could have finished shaving, two massive explosions shook the camp, and for the next three hours a herd of Panzer tanks rolled in to pulverize the ruins. Altogether, the invaders wrought such death, destruction, and havoc as to make resistance impossible. Though Jan and a few other officers remained miraculously unhurt, the uncontrollable state of the horses left the Polish soldiers no way of hauling artillery against the invader, especially since the Luftwaffe kept raining incendiary bombs on the camp.

Since Jan soon realized that retreat was the only option, he and his fellow soldiers were soon reduced to simply wandering east, to get away as well as they could from the Germans. But Jan's wandering eventually took him into the arms of the Soviet Army, which--by pre-arrangement with the Nazis--had invaded Poland from the East on September 17. Thereafter his story is nothing less than extraordinary. Though railroaded deep into the Ukraine and imprisoned there, Jan got himself sent back to Nazi-occupied Poland, escaped his captors by having himself thrown head first out the window of a slow-moving train in the middle of a rainy night, became a courier for the Polish underground, was recaptured during his second trip to France, escaped from a hospital after nearly committing suicide, and--after the fall of France--travelled to England and then America, where he published in English a book titled Story of a Secret State (1944): his eyewitness report on the Nazi invasion of Poland, its brutal occupation (including concentration camps), and the struggles of its Underground. I will have just a little more to say about him at the end of this lecture.

But first I must turn back to the fateful day of September 1, 1939 and its impact on Great Britain. After Hitler launched his invasion of Poland, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain waited one last time for Hitler to change course and withdraw his troops. But after waiting two days with no sign of change, Chamberlain declared war on Germany. One of the more notable versions of that moment in literature occurs in the final pages of a 1942 novel by Patrick Hamilton, a prolific English novelist and playwright barely remembered now. Nevertheless, his novel is worth recovering for the peculiar light it sheds on the mood of Britain in the runup to World War II. Its ending coincides precisely with Chamberlain's declaration of war against Germany on September 3, 1939, which the doomed protagonist hears on the radio just after murdering a man and a woman in her flat. Just why those two events should coincide in the novel is something I'll consider in a moment. But first of all let me back up to the beginning of the novel, which is set in late December 1938, barely three months after Chamberlain signed the infamous Munich Agreement that allowed Hitler to sieze a big chunk of Czechoslovakia without firing a single shot.

En route back to London just after spending Christmas of 1938 visiting his aunt on the Norfolk coast, Geoffrey Bone asks himself:

what had next year, 1939, in store for him? Netta, drinks and smokes--drinks, smokes, Netta. Or a war. What if there was a war? Yes--if nothing else turned up, a war might.

War is one of the many things that divides him from Netta, the femme fatale who endlessly excites both his unrequited desire and his homocidal rage. Like her friend Peter, Netta believed "there wasn't going to be a war at all." Unlike Geoffrey Bone, she and Peter

went raving mad, they weren't sober for a whole week after Munich--it was just in their line. They liked Hitler, really. . . . And old Musso too. And how they cheered old Umbrella! Oh yes, it was their cup of tea allright, was Munich.

Just before spurning their infatuation with Hitler, Mussolini, and old Umbrella, aka Neville Chamberlain, who cravenly traded Czechoslovakia for "peace in our time" at Munich, Bone mines all the implications of the name of his belle dame sans merci:

Netta. The tangled net of her hair--the dark net--the brunette. The net in which he was caught--netted. Nettles. The wicked poison-nettles from which had been brewed the poison that was in his blood. Stinging nettles. She stung and poisoned him with words from her red mouth. (271)

Coursing three times through this onomastic riff on a woman's name, the word "nettles" echoes what Chamberlain said just before he boarded the plane that took him to Munich on the morning of September 29: his third trip to Germany in barely two weeks. Thanks to YouTube you can even now see and hear him saying this:

Just savor his words for a moment: "When I was a little boy, I used to repeat: If at first you don't succeed, try, try, try again. That is what I am doing. When I come back, I hope I will be able to say as Hotspur says in Henry IV, 'Out of this nettle, danger, we pluck this flower, safety'" (emphasis mine).

These words bristle with irony. For one thing, Chamberlain evidently had no idea that someone at the Foreign Office had already concocted a parody of his boyhood motto: "If at first you can't concede, Fly, Fly, Fly again" (Self 321). Secondly, in quoting the words of Hotspur from Shakespeare's play Henry IV, Part I (2.3.9-10), the old statesman flying off again in quest of peace takes his cue--strangely enough-- from a young hothead thrilled by nothing so much as riding headlong into battle, as his name suggests. Having joined a conspiracy to overthrow King Henry, Hotspur gets a letter warning him that his purpose is "dangerous." Though Hotspur testily replies that he will pluck the flower of safety from the nettle of danger, he ends up dead on the battlefield, where his rebellion is crushed. The words quoted by a would-be wise old statesman, therefore, are those of a reckless, fatally self-deluded young man.

In Patrick Hamilton's Hangover Square, Geoffrey Bone is a middle-aged man fatally deluded--again and again--by the hope that he can pluck the flower of love from the nettle named Netta: that he can persuade this dangerous woman to go away with him alone, if only for a few days. Chronically broke because she cannot land anything more than bit parts to feed her acting ambitions, she manipulates Bone with a cunning worthy of Hitler. Just as Hitler lured Chamberlain to various sites--Berchtesgarten, Bad Godesberg, and finally Munich--with alluring promises that he would soon break, Netta repeatedly undercuts the expectations she arouses. First, though she allows Bone to buy her dinner at a posh West End restaurant, her only aim in going is to be spotted by an important theatrical agent; second, though she agrees to spend a weekend in Brighton with Bone (at his expense, of course), she sends him on ahead and then turns up with two other men, one of whom she beds for a night; and third, after agreeing to go to Maidenhead with Bone, again at his expense, she puts him off with a story about a sudden crisis in her family and uses his money for a trip back to Brighton, where she vainly tries to ingratiate herself with the agent. In the end, roused by the "wicked poison-nettles from which had been brewed the poison that was in his blood," Bone takes his revenge by quite literally grasping the feet of the nettle called Netta while she is taking her bath, forcing her head underwater until she drowns, and then killing Peter with a golf club to the temple.

Though Peter is described as a "blond fascist" just before he is fatally struck, I am not sure what to infer from the fact that Bone's last day--the day on which he kills both Netta and Peter and then himself--is plainly identified as September 3, 1939. But in the late morning, when Bone turns on the radio in Netta's flat so as to cover the noise of anything he might do with the two corpses, the (here boldfaced) voice of Chamberlain declaring war at 11:00 AM clearly weaves its way into his thoughts:

'... prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland' he heard, 'a state of war would exist between us...' That was old Neville: he knew that voice anywhere. 'I have to tell you now... that no such undertaking has been received... and that consequently this country is at war with Germany...'

As Chamberlain declares international war, Bone concludes his private war with his tormenters, Peter and Netta, who have relentlessly demeaned and derided him. Since he takes his own life shortly afterwards, his victory is Pyrrhic, but since Chamberlain's own Chiefs of Staff had predicted a two months' hailstorm of German bombs if war broke out (Self 317), Chamberlain's declaration of war may itself have sounded suicidal. Now let me turn to the poem that W.H. Auden entitled, "SEPTEMBER 1, 1939."

Just as Chamberlain's declaration reached the ear of Hamilton's doomed protagonist by radio, radio was also the medium by which Chamberlain's voice reached the ear of W.H. Auden in New York. But Auden first learned of the invasion of Poland from a newspaper, and soon after he started work on a poem that eventually came to be titled "September 1, 1939."1 Unlike Hemingway's novel For Whom the Bell Tolls, which is clearly based on his experience in reporting the Spanish Civil War, Auden's poem is not based on any experience of Poland or even on any news reports of what was happening there--beyond the bare fact that Hitler's invasion Poland had ignited WWII. Yet even though the poem does not even mention Poland, it remains an event in the history of literature as well as of its relation to political history. To see what Auden brought to the making of the poem, I would like first to glance at his earlier life and then scrutinize the elegy he wrote on the death of William Butler Yeats in January of 1939.

In 1929, the 22-year-old Auden spent seven openly gay months in Berlin, whose political ferment and wide-open boy brothels furnished much of the material for his most important poem of the period, "1929" (Deer 25-26). The following year he launched his literary career with his first volume of poems and thereafter gained some firsthand experience of war. In 1937, he spent seven weeks in Spain in the midst of its Civil War (though without meeting Hemingway, so far as I know), and in 1938 he not only travelled to China to observe its war with Japan but thereby gathered impetus for a travel book of prose and verse entitled Journey to a War, published in March of 1939. The book includes a sonnet sequence titled In Time of War (later Sonnets from China). Ranging from the Creation of man to the war in China, with "Shanghai in flames," the sonnets construe "history," as the product of man's unending choices, "the weight of human events" (Auden CP 155, Mendelson EA 348-49). So by September of 1939, when news of war reached Auden in New York, he had already begun bearing witness to the tumultuous history of his times.

Just after reaching New York in late January of 1939, when he was not yet 32, Auden wrote an elegy for William Butler Yeats. By the time he died at the age of 73 in Menton, France, Yeats had made himself not just the greatest poet of Ireland but a poet whose international renown had been confirmed by the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923. Yeats seldom wrote poetry about either politics or historically notable events. But in "Easter, 1916" he commemorates the agonizing birth of the Irish Republic: the abortive uprising against British rule that took place in Dublin on Easter Monday, April 24, 1916. While historians tell us that the uprising was crushed and most of its leaders executed for treason, Yeats's poem captures the irrepressibly lasting impact of the event. On one hand, he voices his aversion to violence and to several of the uprising's leaders, whom he personally knew and hardly idealized: he calls one a shrill-voiced "ignorant" polemicist and another a "drunken, vainglorious lout." On the other hand, he salutes the daring of their deed, which he presciently construes as a birth pang of independence: the freedom from British rule that Ireland would finally gain just a few years later, in 1922. No matter what Yeats had thought about violence or the leaders of the uprising, no matter how much he personally disliked them or how reckless they may have seemed, he now finds

All changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

These powerful lines were surely among the many that prompted W.H. Auden to write his elegy for Years just after he reached New York by steamship in late January of 1938.

Far from the site of Yeats's death in France, Auden views it in light of a New York winter, when "snow disfigured the public statues" and "the mercury sank in the mouth of the dying day." Traditionally, the recompense for the death of a poet is the immortality of his words, which in this case are said to live on in the hearts of his admirers; no matter how "silly" Yeats became or how much he decayed in old age, Auden writes, "your gift survives it all." But the value and meaning of that gift is beyond control of the giver, for "the words of a dead man," Auden writes, "[a]re modified in the guts of the living." In leaving England just as a second Great War threatened to engulf it, Auden might seem to have followed the example of Yeats, who bade farewell to both war and politics near the end of his life. But in his elegy for Yeats, Auden turns him into a prophet of chaos. Just as Yeats's "The Second Coming" had decried the anarchy "loosed upon the world" by World War I, Auden now sees in Europe nothing but darkness, hatred, and canine rage:

In the nightmare of the dark

All the dogs of Europe bark,

And the living nations wait,

Each sequestered in its hate.

For Auden, however, Yeats's poetry remains an antidote to hatred and heartlessness: the "the seas of pity . . . / Locked and frozen in each eye."

In spite of the postwar anarchy that Yeats himself lamented and the prewar darkness that Auden now beholds, he sounds a final note of regeneration:

In the deserts of the heart

Let the healing fountains start . .

If applied to Auden's own life, these lines could be read as forecasting something like a re-enactment of Yeats's turn from war and politics to love. By March of 1939, when Auden's elegy first appeared in print, his literary reputation had brought him invitations to lecture in his adopted city of New York. Shortly after giving a talk on the Spanish Civil War at the Commodore Hotel, he met an eighteen-year-old Jewish-American poet named Chester Kallman and promptly became his lover. He also wrote the first of "Ten Songs" that juxtapose the newly coupled pair with the rumblings of imminent war:

Thought I heard the thunder rumbling in the sky;

It was Hitler over Europe, saying, 'They must die.'

We were in his mind, my dear, we were in his mind.

Perhaps in part to get Hitler out of their minds, Auden and Kallman decamped to California in the late spring for what Auden called "the eleven happiest weeks of my life." When they returned to New York on August 30, he wrote the following as part of the very first entry in a journal-diary that he would keep for the rest of the year:

The prospect of war seems slightly less. It is curious how the knowledge of being loved can change one's attitude so completely. Last September in Brussels, I was really hoping there would be a war: the miraculous Second coming. This year the possibility of having to leave C[hester] if war breaks out, made me burst into tears while listening to the radio-news. I realize that for the last four years a part of me at least has been wanting to die. I say a part, because when I was in Spain and could have joined up, a little voice said, "no." That afternoon at Sarinyena [Sariñena] I realized that the other half wanted desperately to live. It had faith, and how right it was, bless it, though, God knows the bad half did its best to prevent its ever being so. But I wonder how many people there are in Europe who feel as I did last Sept? (qtd. Galvin 29, boldfacing mine).

Here is a fascinating self-portrait of a 32-year-old English expatriate newly in love and newly conscious of how much being so has changed his view of the coming war. Historians will never be able to answer Auden's final question--to count the number of Europeans who felt as much of a death wish as he did in September of 1938. But I think it is probably safe to say that he was part of a miniscule minority. Among the millions in France and England alone who dreaded the coming of a second Great War, how many would have welcomed its "second Coming," as Auden calls it, clearly thinking of Yeats's poem as well as of the Book of Revelation, the Second Coming of Christ, and the Last Judgment of the world? But Auden himself felt deeply divided in the late thirties. In 1937 he was tempted to join the fight against Spanish Fascism at Sariñena, where the Republican Air Force held an airfield until it was lost to the Nationalists in 1938. But even while tempted to join the fight against Spanish fascism, he suddenly realized that he "wanted desperately to live." Since that time, his faith in the possibilities of life had been rewarded not only by the pleasures of love, as he plainly indicates, but also--as he surely implies--by the poetry he had lived to produce. As a pacifist, Auden would never have signed up for combat, and he was such an erratic driver that one of his friends thought it "a mercy for the wounded" that he never even joined the ambulance corps (qtd. Galvin 29). "People have different functions," he told another friend some months after his time in Spain. "[M]ine is not to fight; so far as I know what mine is, I think it is to see more clearly, to warn of excesses and crimes against humanity whoever commits them" (qtd. Deer 29).

In light of these comments, consider what he wrote about poetry in a section that he added to his elegy for Yeats in the early spring of 1939, sometime between its first appearance (in The New Republic of 8 March) and its second (in the London Mercury of April):

Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.

Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still,

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.

W.H. Auden, "In Memory of W.B. Yeats,"

Auden's famous disclaimer (here boldfaced) has been endlessly debated, but its context is crucial. On the one hand, Yeats's poetry has not made Ireland sane, any more than Shakespeare's plays made England sane in the early seventeenth century, when Roundheads and Royalists were gearing up for civil war. On the other hand, Yeats's poetry "survives / In the valley of its making" as "A way of happening, a mouth": a voice that bears enduring witness to the madness of his native land. While Yeats's poetry never cured Ireland's madness or allayed its grief, neither one ever choked his voice, which goes on singing from beyond the grave.

But if poetry makes nothing happen, if no poem can be an historical event, what is its relation to history? The closest Auden came to answering this crucial question was in a 1972 interview:

Write a poem if you feel moved to because of circumstances. But what you must not imagine is that you can change the course of history by doing so. I wrote several things about Hitler in the thirties, but nothing that I wrote prevented one Jew being gassed or shortened the war by five seconds. . . . Because when it comes to social and political evils, only two things are effective: One is political action, of course, and the other is straight journalistic reportage of the facts. You must know exactly what happened. This has nothing to do with poetry. It is a journalist's job which, of course, is very important (qtd. Galvin 39-40).

Unlike poetry, reportage does make things happen: 50 years ago, two young reporters at the Washington Post played a crucial part in ending the presidency of Richard Nixon--as well as making "Watergate" a lasting name for political corruption. But I think it's fair to say that nothing historical--nothing that counts as an historical event--was ever changed by poetry.

Nevertheless, to exclude literature altogether from history, to exclude poetry from the record of global or national "events," is to handicap our understanding of the past. Like the "whole truth" that courtroom witnesses routinely swear to tell, the whole truth of the past can never be recovered by anyone, historian or not. Whether or not any particular poem ever made anything happen, some poems bear witness to the impact of a particular event or particular moment on a mind capable of calibrating its significance at the time it occurred: of saying how it felt then, how it touched a human heart, why it mattered to the human race. While no poem can ever count as an historical event, some poems thus become part of the memorable past.

Consider then the poem that Auden wrote at the outbreak of World War II. By the end of August, he and Chester Kallman had returned from their "honeymoon" trip to California and taken an apartment on 1 Montague Terrace in Brooklyn Heights, looking across the Promenade and the East River to the southern tip of Manhattan. (My own daughter Virginia now lives just a few steps from there.) With an ocean guarding him from the perils of European war, Auden knew very well how lucky he was. On August 31, the day before Hitler's invasion of Poland, he wrote in a journal that he had just begun keeping, "I must never forget that I am probably among the five hundred luckiest people in the world" (qtd. Galvin 24). He felt so precisely because he was keenly aware of millions who were far less lucky. The poetry he wrote in 1939--above all his September 1 poem-- springs in part from his avid consumption of the latest news from all parts of the world. Though not at all a journalist, he listened to the radio whenever he heard it and devoured every newspaper he could find. He not only ingested the news; he curated it, turning it into a journalistic collage. The very first set of entries in his new journal perfectly exemplifies what T.S. Eliot once wrote about the mind of a poet: "constantly amalgamating disparate experience[s]" that are "always forming new wholes" ("The Metaphysical Poets," 1921).

Consider for instance the combination of public events and highly personal experience that Auden records in his journal for September 1, the very first day of World War II:

Woke with a headache after a night of bad dreams in which C. [Chester Kallman] was unfaithful. Paper reports German attack on Poland.W.H. Auden, Journal entry for September 1, 1939

The only thing that would interest a historian in this entry is the German attack on Poland. Yet Auden brackets this momentous event with a morning headache probably sharpened if not induced by jealous dreams about his young lover, whose frequent infidelity would eventually lead to their breakup. Auden thus reminds us that just as war cannot eclipse every other event of possible consequence that may be happening at the same time, it cannot monopolize the thoughts and feelings of everyone, and certainly not of a poet. In forming new wholes from disparate impressions, Auden's entries make up a part, however tiny or "irrelevant," of the memorable past.

Have I abandoned history for biography at this point? Only if history has absolutely nothing to do with the lives of individuals, or with the lives of individuals known for neither political, nor diplomatic, nor military feats. Let us then consider Auden's highly individual take on the outbreak of World War II in the most explicitly historical poem he ever wrote: "September 1, 1939."

In spite of its fame, we must face one awkward fact about this poem: Auden himself came to loathe it. Reading it a few years after it first appeared in the New Republic (18 October 1939) and then in his collection Another Time (1940), he recoiled at what had become its most famous line: "We must love one another or die." "That's a damned lie!" he said to himself. We must die anyway!" (qtd. Fuller 292). As a result, he cut from his Collected Poetry of 1945 not just the lying line but the whole stanza ending with it, and though he allowed the stanza in Oscar Williams's New Pocket Anthology of American Verse (1955), that was its last stand. Even after changing that line to "We must love one another and die," he eventually disowned the whole poem and refused to let it appear in any form after 1964. That is why you won't find it in any edition of Auden's collected poems, including the posthumous collection edited by Edward Mendelson and published in 1976.

Proving, perhaps, that lines of poetry truly deathless cannot be slain by even the poet himself, the original version of Auden's poem--unaltered and uncut-- can now be readily found online.

But why should I wish to revisit--much less try to explicate-- what Auden himself finally called "trash"? In spite of that verdict, I believe these lines still have enduring value. And paradoxically, much of that value springs from their impermanence: their expression of what the poet thought and felt at the time he wrote them. To that extent, they take their place in the cultural history of 1939 as well as the history or biography of Auden himself.

If a poet is always forming new wholes, as Eliot says, by combining bits of his own experience with other events, Auden's opening is a perfect example. While sitting in a mid-town Manhattan dive on a September night, he fearfully contemplates the fate of Europe, where "the clever hopes expire / Of a low dishonest decade." Roughly adapting the short, blank-verse lines of Yeats's "Easter, 1916," he concentrates this moment of history into just nine words. After years of false promises and assurances by French Prime Minister édouard Daladier and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain as well as by Hitler, the "clever hopes" for peace enshrined in the arduously negotiated terms of the Munich agreement have expired. Less than a year after seizing all of Czechoslovakia and thus breaking his promise to take only the Sudetenland, Hitler has killed all hopes for peace by invading Poland. As a result,

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives. . . .

Like almost every other memorable poem, this one springs from many sources--private as well as public. "The day war was declared," Auden said later, "I opened Nijinsky's diary at random (the one he wrote as he was going mad) and read: 'I want to cry but God orders me to go on writing" (qtd. Fuller 291). A few days earlier, Auden himself had "burst into tears" on hearing a radio news bulletin, as he wrote in a letter of August 28 (Mendelson, LA 77). But now he too feels bound to "go on writing" by exposing the contradictions of love even in time of war. To do so, he mines another passage from Nijinksy's diary: "Some politicians are hypocrites like Diaghilev, who does not want universal love, but to be loved alone" (Nijinsky 44). Since Auden knew only too well how war shreds platitudes and abstractions such as universal love and universal peace, he bluntly charges every one of us with hypocrisy:

The windiest militant trash

Important Persons shout

Is not so crude as our wish:

What mad Nijinsky wrote

About Diaghilev

Is true of the normal heart;

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

Behind this passage lies the Most Important Person of 1939, Time's Person of the Year just past: Adolph Hitler, who repeatedly posed as a man of peace while relentlessly preaching "militant trash": the gospel of intimidation and war. And since "universal love" would surely guarantee "universal peace," the former phrase reminds us that Hitler has done everything he can to crush them both with hatred. But ironically enough, this stanza subordinates the Most Important Person to a mass of unimportant persons: each of us. The "normal heart," writes Auden, wants "universal love" no more than Diaghilev or even Hitler does: instead it craves the gratification of being "loved alone," loved exclusively--above all others. Shortly before writing this stanza, as already noted, Auden had suffered a bad dream about the infidelity of his new young lover. While he nowhere alludes to this dream in the poem, he universalizes his craving for fidelity as not only an "error bred in the bone" of all humankind but also as something cruder than the "windiest militant trash" shouted by demagogues like Hitler. It does not matter that Auden's claim is implausible, that the "error" of wanting to be loved exclusively is probably no more universal than love itself, or even that Auden wound up disowning his whole poem, including of course this stanza. In spite of all that, the stanza flouts public--or "historic"-- speech with private truth, baring the anything-but-normal heart of a poet as he contemplates the outbreak of a second Great War.

Yet so far from being purely subjective and therefore un-historic, the poem as a whole is driven by Auden's sense of history. He actually explains the origin of the new war in terms that would be perfectly understood by Hitler himself. Throughout the 1930s, Hitler repeatedly claimed that Germany had a right to retaliate for the humiliations inflicted upon it at the end of World War I by the Treaty of Versailles. So Auden aptly writes, "Those to whom evil is done / Do evil in return." It does not matter if the punishments imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles were justified, or, as Chamberlain and his fellow appeasers thought, unjustified and therefore "evil." Auden is not taking sides here. He simply avers that this war, like all war, springs from the lust for revenge.

Though hardly a dispassionate historian, Auden ransacks the past. Turning back to the father of history in ancient Greece, he claims that Thucydides knew all "the elderly rubbish" spouted by dictators "to an apathetic grave," all "the habit-forming pain, / Mismanagement and grief." Yet even as Auden recalls the pains of the ancient Pelopennesian war, he unmistakeably alludes to the pains of a war still raw in modern memory: "we must suffer them all again."

As war begins anew, then, what then does this poem have to offer? Only "a voice / To undo the folded lie," by which he probably means the folded newspaper borne by the "man-in-the street." Long before Donald Trump denounced nearly all news as "fake," Auden implicitly charges that no newspaper ever tells the deep truth about human existence, especially in time of war:

There is no such thing as the State

And no one exists alone;

Hunger allows no choice

To the citizen or the police;

We must love one another or die. (boldface mine)

In spite of its seeming clarity, the last line of this cryptic passage is the most problematic line in the whole poem--for us as for Auden. For that very reason, we must carefully study the lines that just precede it. The State, he reminds us, is an abstraction with no life apart from the human beings who populate it, and yet paradoxically, none of those beings is self-sufficient. While both citizens and the police are constituted as such by "the State," they are both driven by "Hunger," by the need, instinct, or compulsion to love. Here is part of the reason why Auden eventually disowned the whole poem. Not long after writing it, he came to hate the reduction of love to instinct (Mendelson 477). Yet at the time he wrote it, he was still newly in love with Chester Kallman, newly compelled by a desire that must have seemed the only alternative to the hatred expressed by war. The last line, then, was true to his feelings in September 1939 even though--as a generalization about all of us-- it came to seem flagrantly false.

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet, dotted everywhere,

Ironic points of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages:

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

The final stanza prompts another kind of objection. Since it ends by setting "an affirming flame" against "negation and despair," it courts a charge of poetic compulsion: having envisioned a world benighted and stupefied by war, the poet may feel bound to say something compensatory or even redemptive about "points of light." Yet here perhaps Auden speaks better than he knew. As an English expatriate living more than an ocean away from the bombs and bullets of European combat, as one of the "five hundred luckiest people" in a world newly rocked by the outbreak of a second Great War, he could not have known anything about a young Polish cavalry officer named Jan Karski, who--when the poem was first published on October 11, 1939--was enduring all the privations and brutality of a Soviet prison camp, and would soon thereafter become a prisoner of the Nazis. Yet by the end of 1939, Jan Karski had not only survived his ordeal and escaped from the Nazis but had also vowed to do all he could to revive his native land by working as a courier for the Polish Underground and eventually reaching America, where he published what he called his Story of a Secret State. Viewed by the literary critic, the "affirming flame" of Auden's last stanza might be no more a stock trope, a conventionally "poetic" light against darkness. But had Jan Karski been able to read it, it might well have struck him as a perfect metaphor for his burning aspirations at a time and place of devastation and suicidal despair.

When it first appeared in the New Republic on October 18, 1939, it was titled simply "September-1939." Not until later was it variously titled "1st September 1939" and --in the canonized version--"September 1, 1939" (Sansom 30-31).↩︎